Archive exhibit 2: Eugenics in Popular Culture

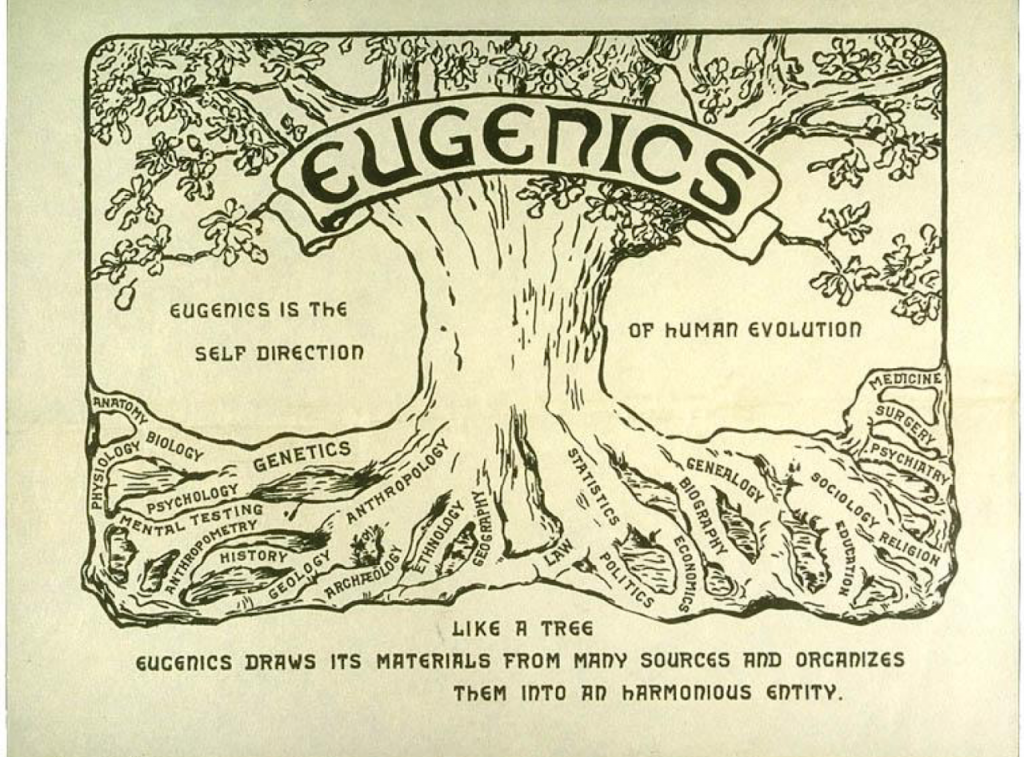

The Director of the Eugenics Records Office (a department of the Carnegie Institution of Washington Station (CIW) for Experimental Evolution at Cold Spring Harbor, New York) biologist Charles Davenport, called for Americans to learn a new doctrine of self-sacrifice rooted in a “eugenic religion.” That religion would depend, he argued, upon healthy individuals fulfilling their duty to have children and “the unfit” abstaining from marriage and procreation. The American Eugenics Society ensured the spread of eugenic anxieties, assumptions, and solutions throughout the country.

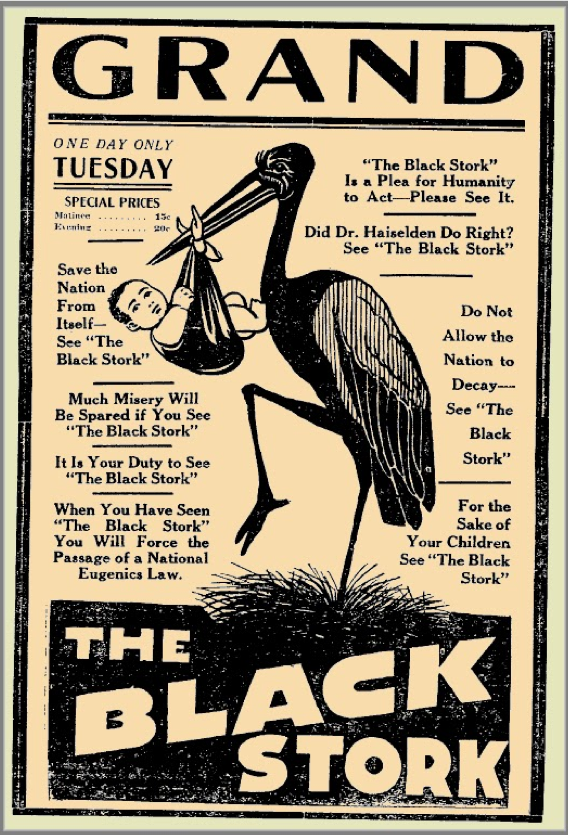

Chicago physician Harry Haiselden created a film called The Black Stork based on his own decision, on eugenic grounds, not to operate on a baby with an unperforated anus (as a consequence the baby died). In the film version of the story, the baby’s father had an inherited disease but ignored warnings that he should not marry. The mother has a dream in which her child lives a life of suffering, and she awakes reconciled to Dr. Haiselden’s recommendation. The film was shown from 1917 into the early 1940s.

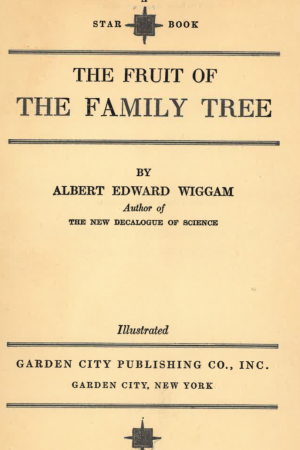

Albert Wiggam spread the ‘gospel’ of eugenics far and wide in books like THE FRUIT OF THE FAMIY TREE (1924) and THE NEW DECALOGUE OF SCIENCE (1922). The latter proposed a “New Ten Commandments” based on eugenics. Wiggam’s work was praised by professional biologists. Princeton biologist E.G. Conklin wrote the following, for example, of Wiggam’s The New Decalogue: “It is a splendid statement of one of the greatest needs of modern civilization – a need so great and so urgent that unless the warning which he has uttered are heeded by our statesmen, educators, and people in general it will mean the decline of civilization and its ultimate downfall.” ~ Century Magazine

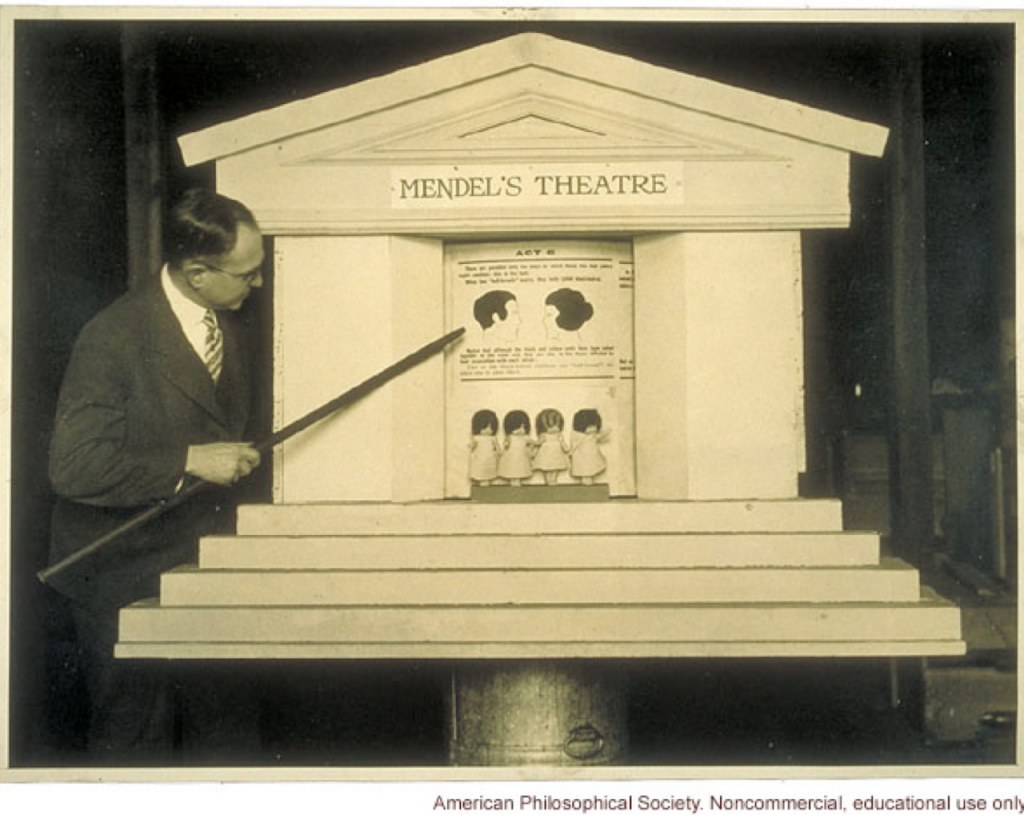

Eugenics Societies organized hundreds of exhibits aimed at educating the public, often at State Fairs. The exhibits sponsored “Fitter Family” and “Better Baby” Contests. Eugenics melded with public health campaigns, resulting in a complex mix of recommendations on how to improve one’s environment while attending to mate choice. By the 1920s, many biologists and psychologists argued that heredity and proper mate choice was the only means of ensuring permanent progress (as compared to improving the environment).

Educational Exhibits

Biologist Charles Davenport, director of the Eugenics Records Office at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York, wrote about eugenics for a range of audiences. A copy of a pamphlet Davenport wrote for the YMCA Health League is in Slater’s Papers in the Archives & Special Collections of Collins Memorial Library. Davenport’s first chapter was entitled “Fit and Unfit Matings” and began: “There comes in a time in the life of most thoughtful, cultured people when they realize they are drifting toward marriage and when they stop to consider whether this proposed union will led to healthful, mentally well endowed offspring. But however much such a person may take the advice of books and friends, he will find much lack of definitive knowledge that, shutting his eyes to possible disaster, he decides to take his chances. Were our knowledge of heredity more precisely formulated, there is little doubt that many certainly unfit matings would be prevented, and other fit matings, that are avoided through false scruples, would be happily contracted.”

Harvard biologist Edward East, wrote books for major publishers on eugenics with titles like Heredity and Human Affairs and Mankind at the Crossroads. James Slater’s student, James Legg, cited East’s Mankind at the Crossroads in a 1947 thesis defending sterilization for eugenic purposes.

Madison Grant’s The Passing of the Great Race, or, the Racial Basis of European History (1916)

While not all versions of eugenics valued certain groups over others, many of the most influential versions did. Madison Grant argued that Europeans were comprised of three separate subspecies, and that those ‘subspecies’ were in competition. Hitler called Grant’s book his bible. The director of the American Natural History Museum (in New York) Henry Fairfield Osborn wrote a laudatory preface to Grant’s book and the book was reviewed favorably in the pages of Science. Other biologists, like W.E. Castle, criticized Grant’s book as ‘racist propaganda.’ Meanwhile, Grant served as vice president of the Immigration Restriction League from 1922 to 1937 and campaigned for laws to prevent ‘race-mixing.’